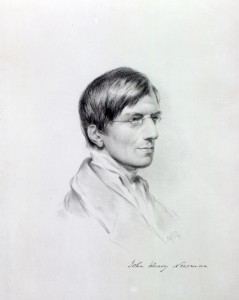

John Henry Newman

Born in London on 21 February 1801, the eldest of six children, he attended a boarding school in Ealing before entering Trinity College Oxford. Despite doing badly in his final exams, he became a Fellow at Oriel College, then the leading college, and soon became a tutor and took Anglican orders. Rather than parish or missionary work, he saw his calling to a life in teaching, and he threw himself into his tutorial and preaching duties. After his attempts to reform the Oxford tutorial system were thwarted, he soon became the leading personality in what became known as the Oxford Movement, a revival within the Anglican Church that sought to bring it closer to the Church of the first millennium and as a result undid many of the changes carried out at the Reformation. His preaching at the University Church of St Mary’s in Oxford made him known throughout the country.

Doubts about the Anglican Church led him to resign his Oriel fellowship in 1845 and become a Catholic. After studies in Rome, he was ordained as a priest and returned to England to set up the first Oratory of St Philip Neri in 1848, in Edgbaston, near Birmingham. He remained there for the rest of his life, i.e. until he died on 10 August 1890, though he split his time between Birmingham and Dublin when founding and running the Catholic University, 1854–58. On leaving Dublin, he was deeply involved in another educational adventure, the founding of the Oratory School at Edgbaston in 1859.

His reputation among his Protestant countrymen, who saw his move to Rome as a betrayal, was largely restored on the publication of the Apologia pro vita sua (1865); and his reputation among Catholics, many of whom regarded his writings and actions with suspicion, was restored with the publication of his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk (1875), which defended Catholics against William Gladstone’s charge that papal infallibility, as defined in 1870 at the First Vatican Council, meant that Catholics had lost their freedom and owed their allegiance to the Pope not the Queen.

Scholarly interest in Newman, as well as popular devotion to him, has ebbed and flowed over the decades since his death in 1890, but his reputation and influence have grown of late – and show every sign of growing further with the prospect of his canonisation and even being named a Doctor of the Church.

Newman and Education

Newman once remarked: ‘Now from first to last, education, in this large sense of the word, has been my line.’ According to conventional wisdom a successful educator is someone who excels either at teaching or at inspiring or organising others to teach; someone who possesses a special talent for dealing with children, adolescents, students or adults in a particular setting, which might be either personal or institutional. What is unusual about Newman as an educator is that over a seventy-five-year period he dealt with every age group, instructing them both individually (in person and by letter) and collectively (in tutorial classes, lecture halls, the schoolroom and the pulpit). The range of his contributions to the organisation of teaching and learning is equally impressive. He reorganised a parish school; played a leading part in the nineteenth-century revival of Oxford University; was the chief founder and the first vice-chancellor of a Catholic university; and founded the first Catholic public school in England.

During his time at Oriel College Oxford (1822–45) he acted as a tutor, lecturer, examiner, dean of discipline and researcher, as well as Anglican clergyman, spiritual guide and preacher. His practical contributions to the reform of Oxford included the introduction of written exams in the college – the University followed suit two years later – and laying the germ of the modern tutorial system by merging the roles of private tutor and college lecturer. But his influence went far beyond these practical innovations and affected the whole teacher-student relationship and contributed to the revival of learning at the University.

Responding to an invitation from the Irish bishops, Newman was the founding rector (or vice-chancellor) of the Catholic University in Dublin. Virtually every aspect of the University which began in 1854 came into being through him, which meant that he devised the curriculum, appointed the academics and led his team, organised the system of lecturing and tutoring, edited the University Gazette, oversaw the finances and administration, took a leading part in the examination system, and, not being content to live in administrative isolation, set the tone by rolling up his sleeves and involving himself in virtually every aspect of its life. He even ran one of the collegiate residential houses that were so emblematic of his pastoral approach to education. The pet scheme of his rectorate (1854–58) was setting up the L&H.

His educational writings

Besides his classic Idea of a university, the theme of education weaves in and out of many of Newman’s writings, including his sermons, which means that it is hard to identify them – especially as he had such a broad view of education.

He regarded the Idea of a university as comprising two of his three main volumes on education; the third was Rise and progress of universities.

His first novel Loss and gain: the story of a convert (1848) is based on his undergraduate days at Oxford and was the first of the genre of university novels to directly link the protagonist’s personal growth to a university experience.

‘The Tamworth reading room’, reprinted in Discussions and arguments (1872), comprises six letters to The Times written in 1841 on the occasion of the opening of some reading rooms by Sir Robert Peel. Newman exposed the fallacy of Peel’s claim in his opening address that reading alone was enough to make men good and virtuous citizens, and his assumption that religion could be replaced by secular knowledge.

Memoranda and other documents relating to his educational ventures can be found in the Birmingham Oratory archive. Much of the material relating to the foundation of the Catholic University in Dublin is published as My campaign in Ireland (1896).

Of the 604 sermons he wrote and preached as an Anglican, two of the earliest ones are remarkable for showing how deeply Newman had thought about the nature and purpose of education, and that he had already discerned in outline many of his key educational principles. ‘On some popular mistakes as to the object of education’ (first preached on 8 January 1826) and ‘On general education as connected with the Church and religion’ (first preached on 19 August 1827) are reprinted in John Henry Newman. Continuum library of education thought, vol. xviii (2007).

Educational themes occur in many of Newman’s letters, which are published in 32 volumes as Letters and diaries of John Henry Newman.

Newman in action

We should admire what Newman achieved in Oxford and Dublin and learn from his efforts to reform education in those two cites, because his achievement shows the extent to which he was able to adapt his thinking to meet the requirements of a very specific time and place, while holding on to what is at the heart of education. His practical engagement shows that he was not just capable of turning out fine phrases and appealing aphorisms, but of setting up, running and reforming educational establishments in ways that are both novel and in keeping with a recognised tradition. Unlike many modern commentators who merely catalogue social ills, Newman diagnoses problems, supplies reasons for why things have gone wrong, and then offers practical remedies.

A broad conception of education

What does the word ‘education’ mean? Newman had a very broad conception of what he meant by the word ‘education’, and he resisted the tendency, common in his time as in our own, to reduce its meaning and narrow its scope. When speaking of ‘education’, Newman would sometimes say ‘education in the larger sense’ to emphasise his use of the word.

Newman did not consider ‘education’ something confined either to its more formal moments or to institutional settings.

Education takes place in formal settings, such as lectures, seminars, tutorials, workshops, laboratory experiments; in semiformal settings, such as drama, music making, student journalism, organised sport; and informal settings, such as meal times and social events.

It is not confined to an institutional setting: someone who did not go to university may end up being better formed than someone who did, says Newman.

There is a marked tendency to reduce ‘education’ to the transition of knowledge, to mere training, and hence to impoverish what it stands for. For Newman, ‘education’ is something much broader as it encompasses the whole person.

In contrast to those who regard knowledge as involving merely an acquisition or a method, Newman views it as a personal possession and a habit of mind, which is why he insists that ‘education is a higher word [than instruction]; it implies an action upon our mental nature, and the formation of a character; it is something individual and permanent’. (Idea of a university)

The concept of paedeia is central to Newman’s thinking, and embraces the total development of the human person.

Why listen to Newman?

Because of ‘the extraordinary quality of Newman’s mind, character, and intelligence. This was someone of high intellectual powers, of notable integrity, someone well aware of the claims of the Enlightenment, a reader of Hume and Gibbon, someone who understood what was at issue in contemporary philosophical debate, someone with a distinctively modern sensibility and literary style, who, at a time when Catholicism seemed to be intellectually impoverished and unable to come to terms with the claims made in the name of secular reason, had identified himself with the Catholic faith.’ Alasdair MacIntyre in God, philosophy, universities (2009)

Because of the ‘modernity of his existence’, ‘his great culture’, and ‘his constant quest for the truth’, three elements which give Newman ‘an exceptional greatness for our time’ and make him ‘a figure of Doctor of the Church for us’. Pope Benedict XVI during his visit to Britain in September 2010

Arnold Toynbee remarked that the fate of a society always depends on its creative minority – and Newman belonged to this minority: his ideas are capable of changing the way we live and think, with important ramifications in particular for the world of the university.

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre remarks that in reading Newman we are confronted with arguments, engaged with insights, and challenged. But a further element to the encounter is Newman himself, who is concerned for his readers and anxious that his words might make them better able to see things as they are. He speaks to us with moral and spiritual urgency, determined that neither habit, familiarity, nor prejudice will prevent us from being open to the truth, including the truth about ourselves. Reading Newman complacently, in order to find only what confirms our existing way of thinking and feeling, is to miss the profoundly interpersonal challenge which he intends. This challenge may influence, surprise, or even upset us. Because he inhabits the same modernity as ourselves, he speaks to our own time in ways which are designed to inform and transform us. This influence unites intellectual, moral and spiritual considerations in ways which are inseparable from the call to conversion. (‘Newman: education, conscience, and faith today’, 2010)

The reason Newman is invoked so frequently in debates about the modern university is that he has much to say, about both its general failings and its pastoral shortcomings. Just as the nineteenth-century journalist R. H. Hutton saw Newman’s writings as a bracing antidote to the influential fallacies of the age’s approved sages, so contemporary observers regard them as a stimulating antidote to the nostrums of today’s academics and administrators and those responsible for the direction and well-being of higher education. A university administrator, lecturer, researcher, rector and educator of public opinion, Newman can address all involved as equals.

Newman has something to say not only to the modern-day research university, but to the liberal arts college, the institute of technology, the medical school, and all the other permutations of higher education. He also gives hope to those pursuing the prospects of a liberal arts college – or indeed a Catholic university – in Britain today. Much can be learnt, therefore, not just from the Idea but from Newman’s practical engagement in education: by seeing how he approached the task, adapted to circumstances, and reacted to crises; what he aspired to in the long run and what he settled for in the short term; even how he dealt with student misdemeanours or their quirky dietary requirements.

‘I mean to be Chancellor, Rector, Provost, Professor, Tutor all at once, and no one else any thing’ may have been a quip, but it illustrates the extent to which Newman had to take on many roles in founding the Catholic University in Dublin.

The story of Newman’s pastoral activity in Oxford and Dublin, as it unfolds in both his actions and his writings, speaks to us about many neglected facets of university life. In times like the present, when the undeniable advances in the organisation of higher education appear to be offset by a misunderstanding of the purpose and role of the university, we need someone like Newman to give us direction and to identify for us the threats to and benefits of true university education.

Drawing on a long-established educational tradition and contributing his own insights, Newman challenges us by pointing out where we have gone wrong and what areas we have neglected; and he also unifies our thinking so as to provide a coherent picture of what the university is about and what it can accomplish, not only in intellectual but also in moral and indeed spiritual terms. In the urgently practical issues that Newman addressed we can see in his response to them the resourcefulness and the wisdom of one of the great Christian humanists.

Newman’s vision for the education and training of the university student – the making of the modern man and woman – is highly engaging. By revisiting his responses to the problems of his age, we can learn from his actions, if not his practical solutions, and apply them to our own age, because his high ideals are also suggestive, adaptable, and inspirational.

Is his vision relevant today?

Despite the risk of attempting to bullet-point arguments that Newman articulated in his highly ornate and nuanced fashion, here are a few reasons why we should give his vision our attention:

To fill the educational vacuum that currently exists today in discussions about the purpose of a university

Because it is all too apparent that economic consaiderations have become the dominant driving force and that much has been sacrificed in the relentless drive for ‘efficiency’

Because the current obsession with targets has aggravated this trend, as the inevitable consequence of institutions focussing on the measurable is the neglect of what is not measurable – which is often closely related to the original raison d’être of the institution concerned

Because of the shameful neglect of the pastoral dimension of the university – that is, of everything that goes on outside lecture hall, laboratory and library

Because Newman’s educational vision, with the pastoral idea at its root, is an ideal foil to the schemes of modern-day planners, since the bureaucratic is the enemy of caritas, the engine of true education

But, why have universities washed their hands of the residential side of university life – and in some cases outsourced residential provision to a private company?

Because the main purpose of university has been overlooked and a narrow conception of education has been adopted by institutions of higher education

Because these matters are no longer regarded as the concern of academics, not least because of the pressure they are under to meet their targets

Because university administrators often have very different priorities, such as boosting an ‘output’ figure for a university ranking-table or fending off anticipated litigation.

In many ways the Oriel common room of Newman’s time is a reflection of our own contemporary establishment, which is populated by establishment men who personify an impoverished view of education and are blind to its deficiencies. The Provost of Oriel was acting for an entire academic ethos in 1830 when he forbade the new approach of Newman and his tutorial colleagues Hurrell Froude and Robert Wilberforce. Newman the educator was looking for something that was absent from the Oxford college system of his day and this is why his pastoral understanding of the tutorial charge meant so much to him.

A fundamental defect of the modern research university prevents it from engaging in radical self-criticism and evaluation of its ends, argues Alasdair MacIntyre. It is because the successful university has lost the ability to think about its purpose and goal that it no longer recognises Newman’s arguments. (‘The very idea of a university: Aristotle, Newman and us’, 2009)

The Idea will surely continue to challenge contemporary thinking on education and to cause discomfort and qualms of conscience to educational administrators.

Newman’s writings are a sure guide to restoring the modern university to its old function as an essential part of social life in a civilised community in the European tradition.